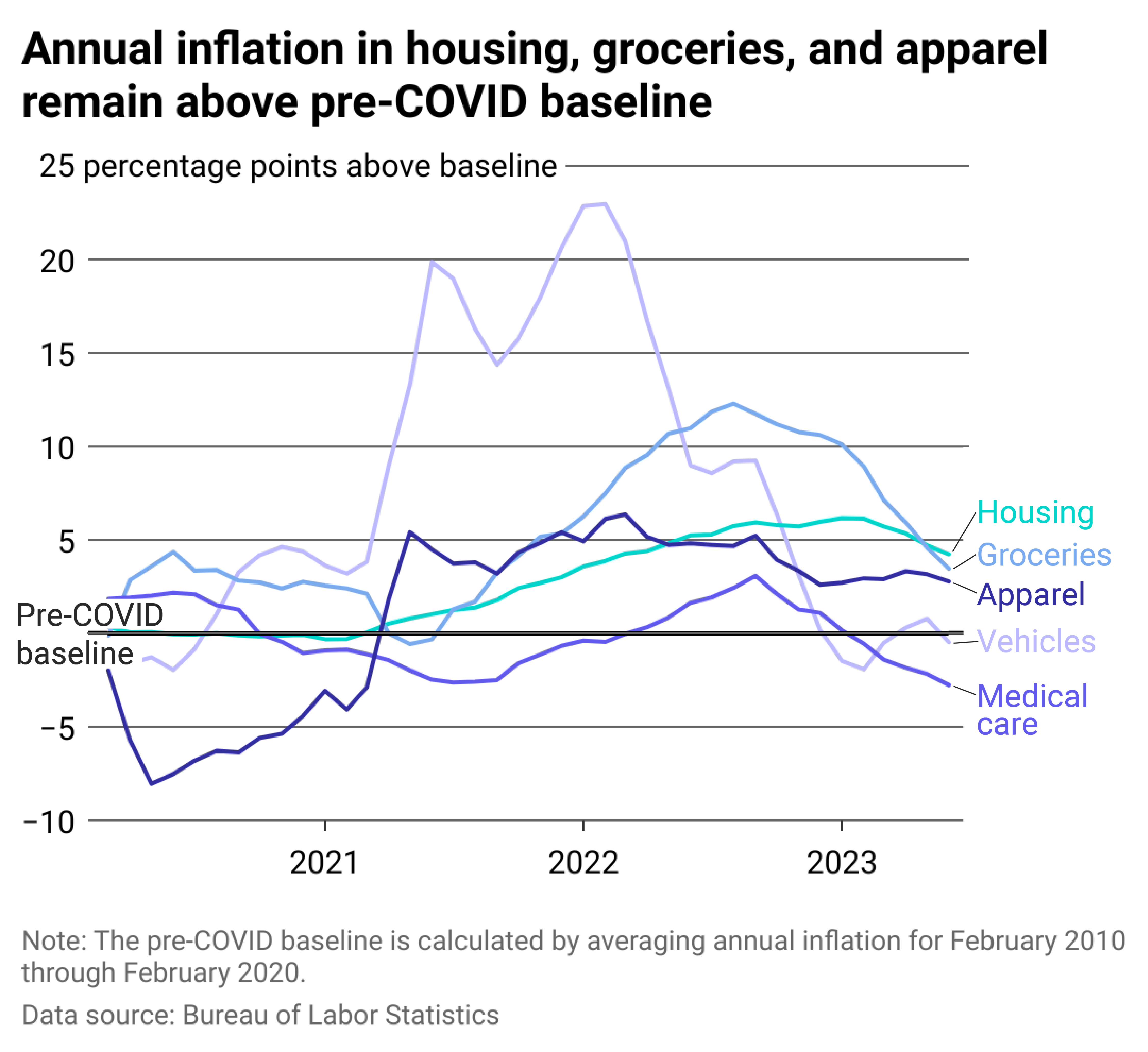

Brandon Bell // Getty Images The Federal Reserve has raised interest rates more than 10 times since March 2022 to stem the high level of inflation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic-era lockdowns, a combination of supply chain crunches, government spending programs, and consumer behaviors contributed to the country’s highest inflation levels in 40 years. Even when the lockdowns started easing and economic demand began to recuperate, the breaking down of global supply chains triggered bottlenecks, resulting in high prices. The phenomenon of sticky wages–where wages rise slower than the prices of everyday items during inflation–made the high inflation levels all the more painful for ordinary Americans. Inflation reduces the value of money, which meant those who were laid off during the pandemic found their savings could buy fewer goods than before inflation. At its worst, pandemic-related inflation hit a 40-year-high of 9.1% in June 2022. To stop it from worsening, the Federal Reserve resorted to interest rate hikes as early as March 2022 to fight inflation. Interest rate hikes help combat inflation by putting brakes on the economy and making borrowing more expensive. When getting new credit turns expensive, consumers spend less, resulting in lower demand–a driver of price hikes when there is limited supply. However, because rate hikes slow down the economy, using them without leading the economy down the path of recession is a delicate balance, an art just as it is a science. Were the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes effective in stemming inflation? Shopdog used Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation data and Atlanta Fed wage growth data to see how effective interest rate hikes were at tempering record inflation. Inflation and wage increase rates are calculated over the 12 months before the reference month. Wages rose to keep up with inflation, which is now nearing more typical levels Shopdog Not all prices change as quickly as others during a recession or inflation. One such price group is wages, or the cost of labor. Theoretically, wages should rise and fall due to market forces. However, several factors contribute to salaries growing slower than inflation–a phenomenon known as “sticky wages.” For one, salaries are often set through agreements with trade unions or employment contracts, which tend to limit wages’ susceptibility to drastic changes. Should there be deflationary pressure on wages, the stickiness benefits employees because while the value of money increases, having the same nominal wage as before means the purchasing power of their salaries increases. The converse can hurt employees during inflationary pressures on prices because until salaries are renegotiated or voluntarily raised, the value of the wages disbursed decreases as money loses its value. During the early half of 2021, inflation overtook the wage growth rate steeply, coinciding with high temporary layoffs that persisted around February 2021, following a spike in early 2020 when lockdowns began. On the other hand, demand continued to rise as many consumers saw they had more spendable funds due to increased savings during the pandemic’s early half, as well as pandemic bailout checks, as the McKinsey Global Institute noted. Due to supply chain disruptions, prices rose with a limited supply of demanded goods and services. The disparity between annual wage growth and annual inflation continued to expand until the Federal Reserve began its inflation rate hikes in early 2022, after which the disparity reached its peak and started decreasing, influenced by other factors aside from the rate hikes, such as the reopening of the economy, end of lockdowns, and gradual restoration of supply chains. In early July, the government reported that inflation reached its lowest level since the first half of 2021 at 3%, 1 percentage point above the Federal Reserve’s goal of 2%. The annual wage growth rate also appears to be greater than annual inflation. Above-average inflation continues in some categories Shopdog Inflation helps measure the rate of price increases in an economy as indicated in changes to the price of a basket of common goods and services households purchase. According to BBC business reporter Hannah Miller, a decrease in inflation translates to a reduction of the rate at which prices rise, not the prices themselves. Inflation also measures the increase in the average price level over time of a basket of common goods and services purchased by households. However, the fall in overall inflation does not mean that prices for all constituent components of the basket of goods and services are falling at the same rates. Several market forces might be behind the reason some goods like apparel, groceries, and housing remain high. Like wage stickiness, some goods exhibit price stickiness, where the market prices do not necessarily fall as one would expect–in theory–to be in line with market forces. Part of the reason for wage stickiness or price rigidity is menu costs–the costs firms incur in changing prices, such as through printing new menus, catalogs, or advertising. Menu costs are especially inconvenient for firms when it concerns lowering prices, for it is a reduction in revenue they could have otherwise received. Another factor is demand. As lockdowns ended and more people returned to offices and attended dinners, business conferences, and weddings in ways similar to pre-pandemic times, the demand for apparel became high. Similarly, for groceries, with more people eating out, events requiring mass catering, and weddings, the demand rises, resulting in high prices in tandem with geopolitical events such as the war in Ukraine, which has caused an increase in food prices in many parts of the world. Likewise, when workers return to offices, they move closer to their work locations. That shift, plus the role of housing as a safe investment, has contributed to a rise in demand for homes, which–owing to limited supply and limits on home construction like zoning regulations–results in higher prices. Data reporting by Paxtyn Merten. Story editing by Jeff Inglis. Copy editing by Tim Bruns. This story originally appeared on Shopdog and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Housing, clothing, and food are more expensive: Inflation of these household expenditures defies Fed rate hikes